There had always been music to accompany film, even in the silent era. Music in movies became a big thing once sound was introduced; now there was another media outlet to peddle tunes to the general public. Radio was better at it, but film was better at selling the singer, not necessarily the song. From Bing Crosby through a thousand crooners to Frank Sinatra, nothing presented a vocalist better than the cinema.

The other and larger part of music for film was instrumental accompaniment. This could re-enforce action, set a mood, comment on the plot, or for simple branding purposes, like the theme songs for Laurel & Hardy of the Three Stooges. It could be commissioned specifically for that production or it could be from a music library. The big studios had orchestras on hand, along with a collection of composers ready to create the appropriate mood. Recording studios were built or large sound stages were utilized it the musicians became too unwieldy.

Instrumental music was more common, for practical purposes. Vocal music, except used under credits, needed to have the singer on screen, lips moving in sync. If there was dialog or sound effects, vocals in the music, the audience was confused. If you were fancy, the music could come from a radio or jukebox, or perhaps a band playing in the background. True soundtrack music had no origin on screen, coming from the imagination of the producers, directors, and musical directors of a film.

Rock sold singles; even Elvis, the King of Rock & Roll, had to wait until his fourth movie to get an entire album worth of songs for a soundtrack, on 'King Creole', one of his best movies. He didn't write the songs any more than he wrote the scripts. After his Army stint, it was initially the soundtracks that sold best, although as the quality tapered off after 'Viva Las Vegas', so did sales. Don't worry, I won't do a dissertation on 'Do the Clam'.

Elvis set the templet of rock in movies, although the copycats in America - Fabian, Frankie Avalon, etc. - could hardly be called rock. Same thing in England, where Cliff Richards managed a soundtrack album two years before the Beatles. But there was another trend that sold albums, not at quite the quantities of show tunes but still at a healthy rate. Some called it Space Age Bachelor Pad music, something to show off the new stereo system. Artists like Les Baxter, Martin Denny, and Esquivel moved units, using exotic images to help attract the young male crowd. It was like Playboy for the ears.

Space Age Bachelor Pad music was only a hot item for about five years. After that, the composers needed to fond work in other fields. If you could do fake Oriental music, you could probably score a science fiction movie. Soundtracks were starting to become more modern; Duke Ellington did 'Anatomy of a Murder' for Otto Preminger in 1959, considered a breakthrough in the use of jazz for a complete soundtrack, not just individual songs. Les Baxter, in particular, moved into low budget movie work and television, as did jazz musicians like Henry Mancini and Lalo Schifrin.

This influenced all other new soundtrack composers, especially the incomparable Ennio Morricone from Italy. Ennio was prolific, used strange orchestration with prominent electric guitar and chorus, and his music was very popular world-wide. Early in his career Morricone was very experimental; nearly all his soundtrack albums are magnificent. A movie with a Ennio Morricone soundtrack is worth watching at least once, just for the surprisingly versatile music and sounds that he used. Pink Floyd would later borrow sounds and textures from Ennio, especially on 'Echoes' and 'Dark Side of the Moon'.

Rock musicals were still stuck in the Elvis mode, even the ones done by the newer generations. The Beatles did the most soundtracks, with 'A Hard Day's Night' in 1964, 'Help' in 1965, 'Magical Mystery Tour' in 1967, 'Yellow Submarine' in 1968, and 'Let It Be' in 1970. All but the last were really half-albums; in the States, where Beatlemania was highest, some of those albums were padded out on the second side with orchestral soundtrack music supplied by producer George Martin. The extra songs, along with single A & B sides, were used to create more product for an insatiable US audience.

Almost everything the Beatles did was a straight song fitted in to a movie, even if they were written specifically for a cinema vehicle, such as 'A Hard Day's Night' or 'Magical Mystery Tour'. It was primitive cross-marketing, songs selling movies which in turn sold songs. The Beatles had mammoth success with their movies; every English band after were desperate to get on screen, every English manager desperate for a deal with a movie studio. The structure of the first two Beatles movies, while certainly hipper and more tailored for the band, featured the group mostly singing on screen or miming to a montage.

'Magical Mystery Tour' was technically a television show, although it had been planned as a feature film to fulfill a contract with United Artists. Directing it themselves, it is an amiable mess, although it does contain the only actual soundtrack work the Beatles ever did; 'Flying'. An instrumental that ambles along with a nice groove, it doesn't sound like anything else the band ever did. The tune was used to accompany a psychedelic montage. As such, it worked fine. Ironically, the film was considered a failure, but it was the first to break with conventions, being more cinematic. While definitely a minor piece with generally weak songs (with a couple of exceptions), 'Magical Mystery tour' showed the effect that psychedelic music was having on the visual representation of songs.

Still desperate to get out of their obligation when 'Magical Mystery Tour' failed to get a theatrical release, the group resorted to a cartoon, 'Yellow Submarine'. There had been a bad Beatles cartoon running for a couple of years; the band understandably hated it. But for the feature, the producer wisely went with a German animator with a more modern style. It used mostly existing songs out of necessity, but parts of it were extremely strong. The four new pieces were one each from Paul, John and George, plus an outtake from Sgt. Pepper's. The Original album still featured soundtrack material padding out the second side.

'Let It Be' is famously miserable, the slow breakup of a band, unreleased on home video for most of the world. It is a curiously mixed bag, started in a movie studio until George quit, then hurriedly finished in the basement of Apple Records except for the rooftop concert. It sat around for a year, no one willing to work on it despite both George Martin and Glyn Johns mixing the music. When the album came out, John and George had given the soundtrack to Phil Spector, much to the anger of Paul, and for good reason.

Spector didn't do 'Let It Be' any favors. It wasn't the strongest collection of songs, but it did have three solid hits from McCartney. Yet one was smothered in strings, 'The Long and Winding Road', sounding more like Laurence Welk than a rock band. Worse still, Lennon's best song from the sessions, 'Don't Let Me Down', was left off, replaced by a weaker left-over from a year earlier, 'Across the Universe'. That song had actually been recorded unsuccessfully twice, once with a wah guitar (hardly ever used by the band) and once with a chorus of groupies warbling off-key in the background. This last version was released on a charity album with little fanfare in 1969.

McCartney was portrayed as the villain of the sessions when instead he was trying to generate some enthusiasm the only way he knew - by trying to lead the band. George was pissed at the lack of material making it on to albums, Lennon was in a heroin fog with Yoko. The book 'Get Back', paraphrasing the transcripts of all band chat between songs for the thirty days of the 'Let It Be' disaster, paints different picture; George quitting after calling Yoko a 'Japanese monkey', Peter Sellers trying to buy heroin from John and Yoke, Paul and Ringo out of ideas how to save the band. The movie is likely not to see the light of day as long as McCartney lives.

In the wake of the Beatles, rock movies flooded the market. Most were horrible, especially in America, where Hollywood wouldn't let a real rock & roll band anywhere near a soundstage. In the late 1950s it was horrid stuff with John Saxon and Sal Mineo, morphing into Fabian and Tab Hunter the next decade. It wasn't until 1967, when Los Angeles groups like the Turtles and the Byrds were able to slip a song into a soundtrack to add hipness to an aging movies business in movies like 'Guide to a Married Man' and 'Don't Make Waves'. It didn't help.

In England, managers could get groups a guest spot in a movie easier. Herman's Hermits even managed a couple of movies in emulation of the Fab Four. Most bands simply lip synced a song, from 'The Ghost Goes Gear' to 'Gonks Go Beat', just as dreadful as the stuff from across the pond. All this stuff, wherever it was made, was low budget, having a shelf life of six months.

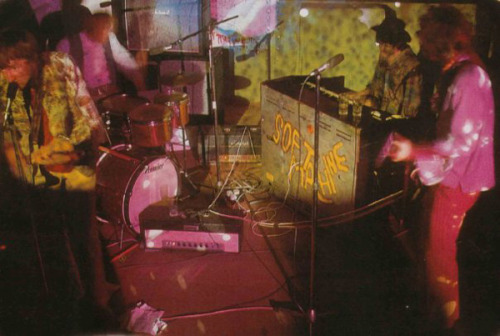

The Electric Flag, a supergroup of sorts formed in Chicago but quickly moving to the West Coast, did a full-fledged instrumental soundtrack to Roger Corman's 'The Trip' in 1967. It sounds not unlike Ennio Morricone's experimental work from the same period, making it the first full-length work done specifically as background music for a film. It was typical of Corman to find an effective low-cost way to score his film, most likely getting input from stars Peter Fonda and Dennis Hopper. It is effective but disjointed, as a soundtrack movie would be, individual pieces written for specific scenes.

Pink Floyd did provide music for a film the next year, but it could hardly be called a film score. There is one meandering piece in 'The Committee' recorded early that year, one of David Gilmour's first sessions with the band. Never released, it's not very impressive, unlike Arthur Browns' performance in the same film, flaming bowl on his head. Manfred Mann got there first, doing a fully realized soundtrack for 'Up the Junction' that same year, another one in 1970 for Jess Franco's 'Venus in Furs'.

George Harrison also provided a complete score for the movie 'Wonderwall', although there is some controversy over it. Paul McCartney had actually beaten him to it a year earlier with 'The Family Way' but it was a traditional classical score. Considering Paul's lack of musical training, George Martin came in to orchestrate and conduct. Harrison produced and takes all writing credit on 'Wonderwall', but the Indian material sounds like sessions musician in Bombay while the rock music sounds like session musicians in London. None of it sounds like Harrison.

Back in America, authentic rock music was starting to seep into movies. Exploitation like 'Riot on Sunset Strip' managed to include songs by the Standells and the Chocolate Watchband, but is essentially a movie for middle class parents about the horrors of the youth movement. 'Revolution', a documentary about San Francisco, managed a great soundtrack with the Steve Miller Band, Quicksilver Messenger Service and Mother Earth, while the movie also includes Country Joe & the Fish. It's pretty obscure but worth tracking down.

The Monkees revolted against their Prefab Four image, producing 'Head', a wonderfully entertaining exercise in career suicide. Completely non-linear yet somehow circular, it has some of the best music of their career. These guys wanted control of their image and their music; 'Head' reflects 1968 America from a youth perspective better than any other film that year. Scripted by Jack Nicholson, the plot is a romp through popular culture, rambling around back lots, making a mockery of television and movies.

'Head' was ahead (ahem) of its time, a truly creative attempt at doing something different with film. Unfortunately, it completely alienated the Monkee's existing audience without attracting a new one. The traditional movie studios in America, which also bankrolled the European film industry in large part, was in collapse, the stars, directors and moguls old and out of touch, attendance in free fall. A rock soundtrack, in part or complete, seemed like a good idea during these turbulent times. A lot of strange ideas were about to get a green light.

No comments:

Post a Comment